Camouflage

In 1996, Tim wrote ‘Brassey’s Book of Camouflage’—the first book to tell the entire story of camouflage uniforms. It stuck a chord with the fashion industry and was a hit among design students, with Tim appearing on the BBC TV Clothes Show.

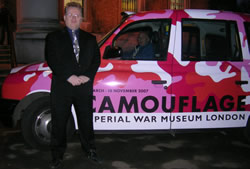

He has continued his research into the history of camouflage and in 2007 he was the author of ‘Camouflage’ (Thames & Hudson), the book accompanying the Imperial War Museum exhibition, the first to show the entire history of camouflage from the First World War to its impact on contemporary fashion.

He has continued his research into the history of camouflage and in 2007 he was the author of ‘Camouflage’ (Thames & Hudson), the book accompanying the Imperial War Museum exhibition, the first to show the entire history of camouflage from the First World War to its impact on contemporary fashion.

These two books, plus ‘The Future of Camouflage’, a catalogue of Tim Newark’s innovative camouflage paintings, are all for sale on Amazon.

Text not published in ‘Camouflage’

Early Camouflage

There’s a further letter in The Times from April 1939 from a former Royal Engineer subaltern who was involved in painting an overseas concrete coastal gun emplacement in “fairly vivid colours, but the disguise was quite effective some distance away”. The year of this was 1886. He claims it came as orders from the War Office, which matches exactly the year of Sir Andrew Clarke’s report on camouflaging gun emplacements in the National Archives at Kew. Maybe the French are the fathers of modern camouflage, but the British may be the grandfathers!

Camouflage Artist

Sometimes when artists takes their visions of camouflage art back to their military source they find a conflict of interests. English artist Paul Gough was commissioned to produce a commemorative painting for the Royal Artillery. As part of the process, he produced a series of sketches of armoured vehicles, which he showed to the officer in charge of the project. On one occasion, he drew a mobile missile launcher.

“The Striker just doesn’t look three dimensional”, said the critical Major.

“That’s because the metalwork has been painted with disruptive camouflage,” replied Gough.

“But it does not look three-dimensional,” insisted the officer.

“That’s because the camouflage effect flattens the form.”

“I appreciate that, but it just does not look three-dimensional.”

So, for the purposes of the painting, Gough painted a strip of light tone to accentuate the nearside bulwark, to make it look “three-dimensional”. In commemorative art, the officer did not want his vehicle disappearing into the North German landscape.

In the Future of Camouflage

Introduction from ‘The Future of Camouflage’

Every city, every neighbourhood should have its own camouflage pattern. When the Soviet Union collapsed at the end of the 20th century, the newly freed peoples rushed to express their national identities by creating new flags—and new camouflage patterns. Camouflage is the new heraldry. Taking elements from local culture, landscape and history, a new pattern arises. In nature, animals evolve a camouflage pattern derived from their environment. My paintings point towards a future in which people can take the principles of camouflage to express their own local identity.

Disruptive Patterns

Camouflage is not about being a chameleon. It’s not about changing your identity to suit a background. It’s not about disappearing. It’s about wrong-footing the observer.

When military camouflage evolved in the First World War, it was quickly discovered that it is impossible to make a vehicle or a big gun or people merge with their background. This can only be achieved by using local foliage to smother an object and this effect is lost as soon as it moves. An aircraft or ship cannot maintain a colour scheme identical to its background when the background is constantly changing. In nature, this is also true of fast-moving animals—predators and grazing animals move too quickly to merge with their landscape.

The solution is to create a pattern that breaks up the profile of a vehicle, man or animal. This primary rule of camouflage is called the Disruptive Pattern. By employing dark and light colour blocks next to each other, the expected shape of the camouflaged object is broken up. At a distance, a camouflaged man does not look like a man but a conglomeration of random shapes of light and shade. A jaguar’s fur recreates the illusion of sunlight breaking through leaves.

In the First World War, enormous battleships were effectively camouflaged by being covered in Dazzle patterns—these were outrageously bold modernist creations in which the usual expectations of light and shade were confounded by enormous geometric patterns painted across the ship’s hull and superstructure. The result was that submarines could not tell at a distance what size ships were or even in what direction they were sailing. They could see them, but not understand them and, as a result, could not effectively destroy them. Camouflage saved lives…

To read more, see ‘The Future of Camouflage’